Clara Mohammed-Foucault’s Perspective

Michael Gabriel Cozier was born in Icacos, a small fishing village at the south-westernmost tip of Trinidad and Tobago, just off the coast of South America. After writing many books and short stories inspired by the folk culture of Icacos and his long career as a boat captain, he is profoundly attached to this village, where he still has his home.

Clara Mohammed-Foucault, a bilingual writer now residing in France, lived in Icacos as a child, and her family were close friends of the Coziers. She has immensely enjoyed reading Michael Cozier’s books. His genius and outstanding talent inspired her to write the following literary review of his works.

Entre l’éden et l’enfer –– le génie de Michael Cozier

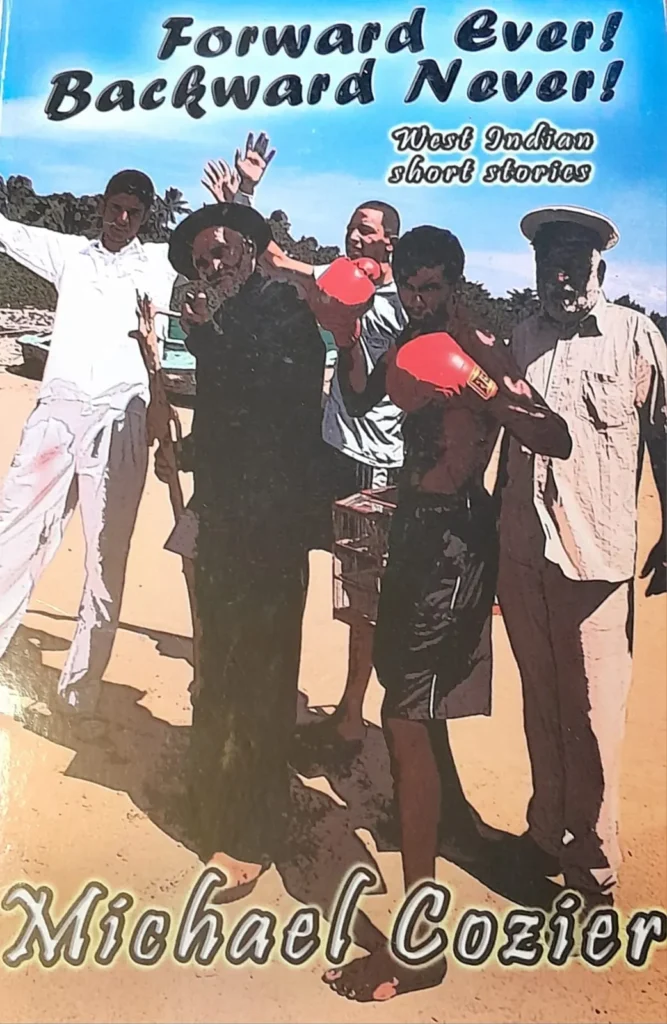

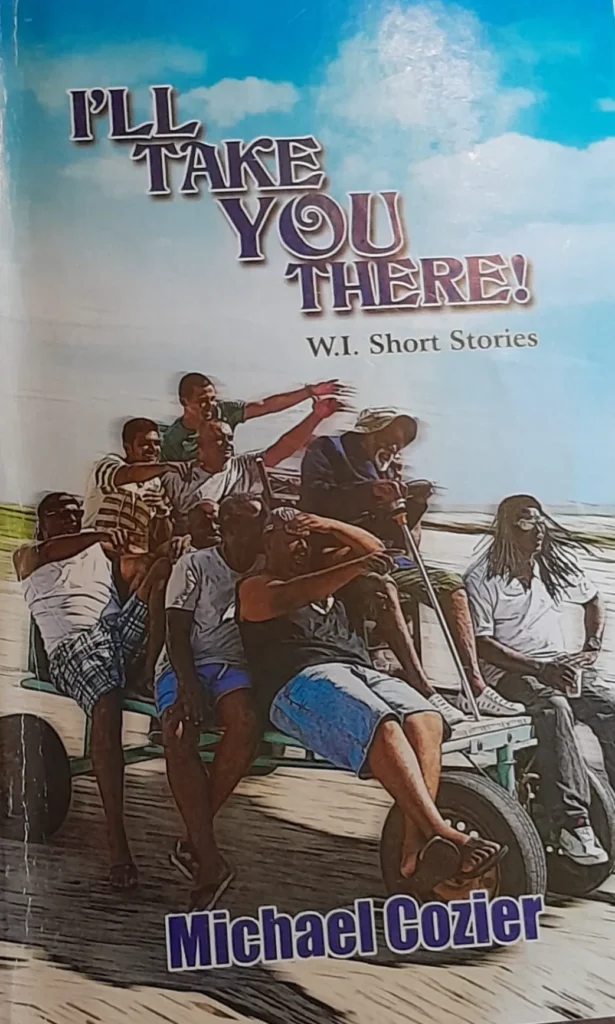

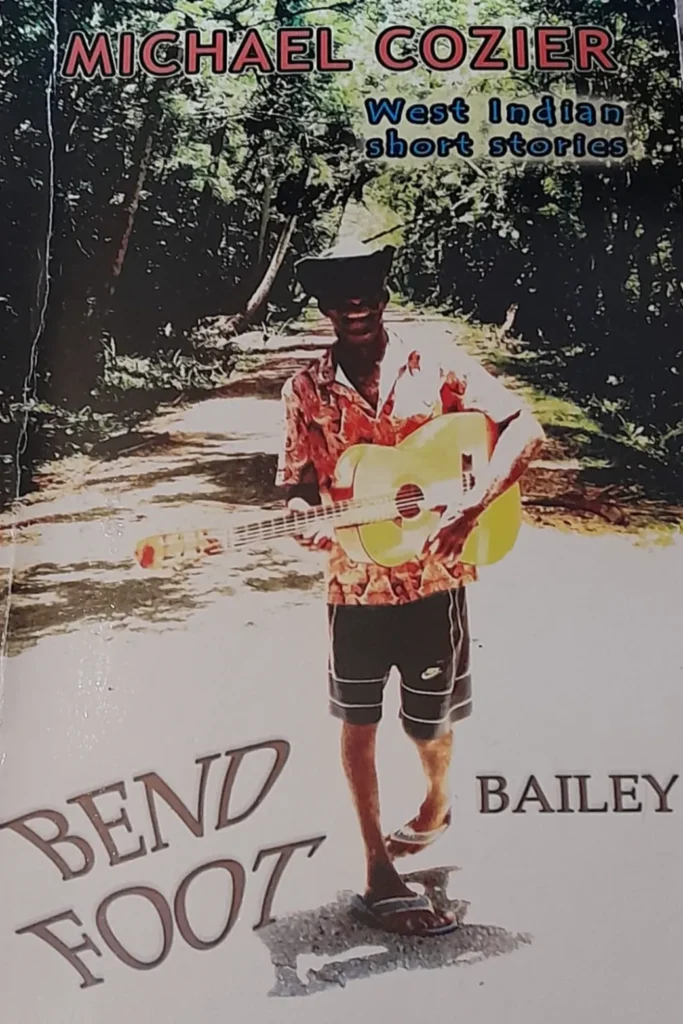

References—PR, Putting up a resistance; OMY , Out of murky waters, BFB, Bend Foot Bailey; FEBN, Forward ever, backward never; NS, The naughty strike, TYT, I’ll take you there.

[PR, Opposer une résistance ; OMY, Sortir des eaux troubles ; BFB, Bailey au pied tordu ; FEBN, Toujours de l’avant, jamais reculer ; NS, La grève coquine ; TYT, Je t’y emmènerai.]

To most citizens of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, the towns and villages located in the Serpent’s Mouth—Icacos Point, Icacos Village, Columbus Bay, Bonasse village, Cedros, Erin; and the inland villages of Chatham, Fullerton, Guapo, Coromandel and Cap-de-Ville—are nothing but behind-God’s-back ink smears on the map of Trinidad. Apart from their dubious appeal as picturesque fishing villages for any Trini dodging the law or in need of a quick hideout, nothing of substance happens or could happen in those places. They err. In his novels and short stories inspired by those same mesmerising stretches of coconut palms and chip-chip beaches, Icacos born-and-bred author, Michael Cozier, gives the lie to that perception.

A second bouquet of exotic-sounding place names, part of the island’s romance, fires our imaginations back to pre-1797 Spanish rule and the Cedula: Bourg Grandchemin, Tabaquite, Rancho Quemado, Palo Seco, Lopinot, D’Abadie, Rio Claro, Carenage, Mayaro and Tamana. If Cozier’s writings are first and foremost an ode to Trinidad, to its skies, seas, sounds, winds, colours, perspectives, sights and touch, no less are they a testimony to the syncretic culture of its people—African and Indian rhythms of the drums during the Hosay festival; the Mont Carmel bazaar and ball as celebrated in Cedros and Icacos. No longer are people shut into their separate myths but blend into an eclectic emulsion where the aesthetic takes precedence over all else in a constant upward thrust.

No borders

Cozier’s wide-ranging talent spans diverse literary genres—the short story; the novel; and thrillers written in the terse style of a film script cum storyboard (“Raid across the border” (BFB)). In this universe, Trinidad is once again a part of South America. All borders are erased—the invisible world is no less peopled than the visible—if a la diablesse tries to carry away Grandpa Cedeno, Amera the soucouyant is caught by the dawn and Ma Coot gets the better of Franklyn’s “negromancy” with her rosary and holy water. La Bruja’s voodoo cock sacrifice from over the waters in Capure deals with Chaitram’s enemies Manbode, Rambir and Padam who promptly follow one another to their grave. Dreams too, are interpreted for whatever they are worth.

Time and space

The Trinidad we know comes alive with casuarina, almond, soursop, immortelle, cedar, Cousay Mahoe, cocoa and coffee and the priceless bois bandé Perez uses to manufacture his snake venom; nor are mango trees just trees: they abound in rich varieties; bush is either a picker patch, black sage, fever grass, shining bush or carakeet. As for tracks, when they are not dirt, they are of chip-chip shell or pot-holed pitch. In most of Cozier’s works, the plot largely unfurls within the confined spaces of the beach, a single street made of chip-chip shells and its combined fixtures of the Chinese shop and rum-shop where men congregate, but in others reaches out to nearby villages in the peninsula—Fullerton, Coromandel and even maps the length and breadth of the islands through Couva and even as far as Roxborough in Tobago.

Deceptive

Among Cozier’s literary feats is the skill with which he matches deceptively simple carnivalesque techniques via the oral idiom of folk culture with sweeping psychological, social, moral, political and spiritual questions. Inter-ethnic prejudice; love and marriage which disregard ethnic differences; petty crime; conmen and impostors; out-and-out violence ingrained in the society as in Raid across the border; prostitution; the institution of the village rum shop and its faithful customers; horse-racing villains; wappee and whe-whe; drug traffic; Rastafarian values; and disability are themes which come under scrutiny.

Jatulal and Belinda (PR) assert their freedom, refuse to live stereotyped lives straitjacketed by racial prejudice and social formulas, nor do they attach a jot of importance to “what people will say”. They shape their lives in accordance with their own feelings. Their victories both as persons and as representatives of their community affirm their unique “Caribbean-ness”.

Fowl thief and ladies of the night

The bottom line is that “everyone must eat” as Mangro mutters to himself when a vulture swoops down on a dead fish. Logic demands that he proceed to help himself to Ma Bethel’s avocados and subsequently bag a duck and a fowl. The single mothers, “ladies of the night”, for their part, who end up at The Pressure Cooker (specialising in…er…salt fish,) in Cedros do a brisk business—everyone must eat—but they wholeheartedly support the striking women (NS). The cause of the fallen woman and single mothers constantly crops up in some of the characters portrayed.

Raid across the border

Only Trinidadians who have lived in Icacos can begin to understand the lawlessness of that miniature world of the 1950’s, now anything but a closed chapter. For the average Trinidadian conditioned to relate to Europe and North America as poles of attraction, the South American mainland is a vague geographical space. “Raid across the border” (BFB) catapults us back to the stark realities. The plot unfolds through a series of quick gestures, movements, glances, commands and execution of commands, all occurring in a milieu where nothing ever seems to happen or can happen yet is fraught with danger and lawlessness. Two poles of experience clash—nothing happens, then the unimaginable happens.

The lingo

If Cozier’s medium for the most part is the oral idiom with the familiar twists and turns of the Trinidad-Tobago lingo, non-Trinidadian readers will no doubt reach in vain for Lise Winer’s dictionary. Certain highly specialised terms defy translation: obzucky, rambunctious, bazoodee, cunumunu, macomère, infracturation, ambeeyance, silloette, soodonim, too-tool-bay, tuncy wuncy—a list by no means exhaustive. Cock’s comb? Cock’s chrome! Write what you hear.

With unsurpassed literary freedom, local parlance translates “samaan” tree to “salmon” tree.

Balo speaks Hindi when he first meets Jatulal. Tipsy Badloo sings the latest: “Janewale doolahana…” and Boboy’s destiny hinges on his not-quite-right Spanish when he tries to purchase an ice cream from Consuelo. Prejudice, ingrained in the society, is not only inter-ethnic: small islanders are supposedly inferior to any Trini: “…the first mistake the boss make is he hire a Grenadian feller…You know Grenadians can’t measure…” Trinidad’s familiar dramatic paradigms are marshalled: the Trident Supervisor “take one look at the mess and tell the contractor to “run, disappear, hide…”

Shifting registers

Peppered with volleys of Trini cusswords but with the characteristic literary freedom which is his by right, the reader hardly notices the shift to a standard English register as in “The investigation”(FEBN). If Cozier’s voice is the authentic oral folk voice, the same voice becomes grammatically self-conscious. Granny, in “More questions than answers” (BFB), rises to the occasion, affirms self-importance and authority with her well-placed s’s:

“…Like you gets you head all mixed up, son.”

“…I tolds you gambling is an abomination of the Lord.”

“So that is the kinds of idolatry you does be up to…”

“And you wants to marry a girl like that?”

A house for Mr. Balo

The house and displacement tropes resurface in Cozier’s works—Balo, too, is building a house with materials thrown up by the sea. Overseer Brown burns the house. Looking at the devastation, Balo tells Jatulal: “I will build it again.” In that simple statement expressing resilience lies the only way forward for the colonised peoples of the world—reject the victim posture, gird up our loins and “build it again”. The Icacos village women who stage a “no salt fish” strike (a local adaptation of Aristophanes’ Lysistrata?) win their cause by coercing their menfolk into putting a stop to their whe-whe gambling.

The artist’s role in society

The artists—Belinda, Mr. Smart the story-teller, Tanzie the calypsonian, Copay the gospel singer—function as agents of social upliftment via a higher level of consciousness of the rights and wrongs at play in the society, of their own and the community’s shortcomings. As for the character Wilhemina, she attains full poetic heights as mistress of the art of “throwing words”; nor is her archenemy, “marga” Surujdaye backward when she resorts to the picturesque similes of Wilhemina’s “big fat obzucky self” and her “two oversize breadfruit”.

The story within the story, as it were, frees the writer of any responsibility to take a stand on social and economic issues. Mr. Smart said so, I didn’t.

Journeys in awareness— some good in me?

Many of Cozier’s characters journey from a marking-time existence to budding self-consciousness and eventually to self-fulfilment. If their journeys capture our attention and are loaded with psychological, social, political and spiritual statements, the culture of laughter which flows from the carnivalesque genre of Cozier’s writing accompanies these same journeys as the characters stumble and fall along the way.

Running thread-like through these narratives is a key psychological process—the capacity of one person to reveal another to himself or herself, even an entire community, to act as an agent of fate. Therapy and personal fulfilment follow in the form of sports or the arts—cricket and football serve as the instruments headmaster Percival Hill and Father Thursday use to awaken their students and the entire Icacos community to themselves. Similarly, Pedro Silva is taken in hand by Ras Lessy and his spouse Empress Naomi who foster him to unleash his resources and make his way towards a brilliant career. The process works both ways—Ras Lessy, alarmed when Pedro gives him weed as a present, is awakened to his immense responsibility for Pedro’s safety, stops smoking weed and also scores a personal victory.

We may also read a success-failure paradigm in the corpus of Cozier’s works. Whatever promise life holds for anyone may either be fulfilled or betrayed by either wilfully spending one’s life wallowing in “murky waters” or developing sufficient self-awareness to scramble out of such waters and surpass one’s self. Arthur brings Sonny Preston to stardom. Gardening becomes a therapy for Frieda Prieto who joins Mangro’s family.

Pundit and pastor

The distinction between genuine power and the trappings of power is yet another issue at play in these narratives. Overseer Brown can only rely on his whip and his abuse of the estate workers. Genuine power is in the hands of the workers. The Watson-Brown whisky evenings on the verandah are only the trappings of power. Their collapse, when it comes, is total.

Religion only too often provides a space for the conman’s resourcefulness, whether impostor Pastor Dudley’s or car thief Pundit Ramsahai’s. If both church and state fail to second the individual’s ambition to rise above his or her condition, the modernity of Cozier’s works lies in what may be termed an existentialist approach to life whereby human beings use their personal freedom to journey from an imposed and conditioned static mode of being to a dynamic one of becoming whereby they take ownership of their own destiny and empower themselves in the process.

Who is you father?

Masks, like nicknames, allow us to try out diverse identities. The Trinidadian capacity for fantasy and different types of masking remains fertile: the Trident supervisor’s name is no less than John G. Kennedy and the debt collector puffs up his chest and walks “like Arnold Schwartzanigger.” The colourful mosaic of nicknames strewn over Cozier’s pages lock people into a caricatural identity—Force Ripe Man, Mangro the Mongoose, Zip Mouth Doreen, The Skipper, Mad Dog, Battle Axe, Fancy Crapaud, Sailor, Wahoo and Chaka, Sinbad the Sailor, Toto Crab, Santa Flora, Tax, Crevedo; not to mention Guava Root, Lagoon Shark, Red Ganze, Gandy, Jupiter, The Squirrel and The Pest. A young man stranded at night in Cedros earns himself food and shelter: “Who is you father?” “Whiteman.”

Poetic justice

The virtuous rewarded? The “bad guy” punished? Overseer Brown and Watson get their due? The pundit unmasked as the vulgar car thief and caught by Sergeant Talbot? The pastor unmasked? Only to some extent does poetic justice apply in Cozier’s works. Against a backdrop of the stock image of the sea-sun-sand-laughter of the Caribbean island, a sombre tragic underside leaves us deeply disturbed. No human agency is ever bestowed the power to deal with the nightmares of piracy and the constant threat of death by drowning which the Icacos fishermen face daily in eking out a precarious living. In one such attack, Bolo drowns: Bolo, the young man “who walked in joy and laughter…Now Bolo was just a bloated piece of flesh that sea scavengers were feasting off.” Junkers sinks into the Davy Jones’ locker trying to save Lando (FEBN).

High comedy—graves and coffins

Only laughter provides relief, so much so that not even death becomes a solemn occurrence. Another of Cozier’s talents is the ease with which he shifts from Mrs. Lakpatia’s irreverence for the dead to the pathos of “The strong angel” (BFB) where the narrative voice once again shifts to standard English.

Mrs. Lakpatia says of her departed spouse:

“…he dead like a semp, with he two foot in the air.”

Lazarus runs a brisk casket-stealing business which is almost the undoing of Frankie, while Ebennezar Trotman successfully converts from coffin-maker to pirogue-builder. (FEBN).

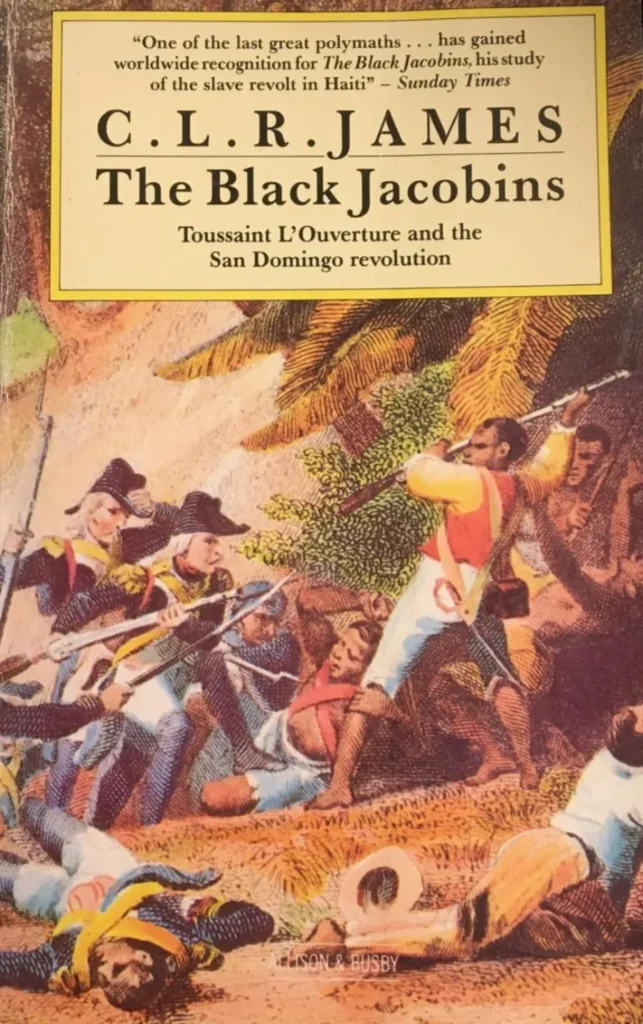

Our laughter stops when we read “The strong angel”, the same kiff-kiff laughter of the West Indians in Selvon’s The Lonely Londoners:

“Under the kiff-kiff laughter, behind the ballad and the episode…a great aimlessness, a great restless, swaying movement that leaving you standing in the same spot.”

Perhaps our very laughter reveals something about us?

Divide-and-rule

A Gargantuan banquet of creole fare bubbles in pots—black pudding, breadfruit and pigtail, mauby, cow-heel soup, Mama Gladys’s fried fish, fried bakes, fish broth, chicken pelau, sweetbread, cocoa tea and the ubiquitous sugar cake and fudge. The cultural ethnic divide yawns: “chulhas blazed away on one side… columns of blue smoke rose from coalpots.” Wilhelmina is proud of her salt meat fare:

“Yeh boy Tanzie, salt meat in we rice and peas. We eh cheap like dem Coolie and dem, only eatin ponkin and roti.”

Capitalist forces

Between 1960 and 1964, no less than 230 strikes were staged in Trinidad. Before he decides to lead the strike on the estate, Jatulal studies his father’s notes (PR). Lucia visits her nephew Jonah, president of “de Trident Base Union in Point Fortin”, for advice about how to stage a strike. Cozier’s narrative Putting up a resistance as well as Seuklal’s lifelong struggle to acquire a pair of a certain brand of shoes and his eventual failure (“The elusive shoe”(FEBN)) bring to mind people’s relationship with the capitalist material world, with objects of desire, deprivation, acquisition and their relative impact on people’s happiness or unhappiness.

The way human beings relate to the earth is a theme which courses through Cozier’s works. An abundance of aquatic and land life is portrayed alongside humanity—king fish, red fish, carite, crau-crau, blue crab, conchs, snappers, cavalis and grunts, Rhode Island fowls, sheep, bulls, cows and scarlet ibises all co-habit with the people of the Icacos sands in a symbiosis.

Imagery

Sounds, sights, textures, shapes and colours abound in Cozier’s writing. Be not afeard, this isle, too, is full of noises, sounds, and sweet airs. Donkeys bray. Cocks crow. Cars go “whish, whish”. Frogs croak. Owls hoot. Bruce Lee wields his Samurai sword: “Whatap! What! Whap!”

If Cozier’s writing is grounded in the carnivalesque tableaux of estate life and the vicinity of the rum shop, poetic flights abound, even if they teeter on the brink of irony as the self-conscious author winks at us. Belinda and Jatulal “sat staring at the trembling ribbon of light cast on the water by the slender moon,” a cool sea breeze “oozed into the room” and “Dewdrops sparkled like tiny diamonds on leaves and grass everywhere.” The sun rises? A “crimson glint” creeps into the landscape. At night the sky is alive with “celestial lights”. Sunset? “The sun traded its yellow sheen for lava red as it slipped behind the far off sea.”

Two tropes maintain a certain tension in Cozier’s writing: one of light which celebrates the Eden of an erstwhile island, another of collapse, grime and dinginess as Eden slips into inferno. Disquieting signs sound a warning conveyed in the imagery itself. A precarious world falling apart is symbolised by Tewarie’s shop: “Its rusty galvanised roof seemed to be slipping off…”.

Is the whole island rusting? When the very elements are hostile to the village’s materials, a legitimate question arises: can this village, this very island, aspire to any permanence?

Po-me-one? Not me!

Cozier’s works are a total denial of any suggestion that moral stagnation is a fatal result of the colonial legacy. His works not only furnish us with a mirror which reflects incomplete lives and their accompanying fantasies of self-fulfilment but achieve the far greater purpose of any artistic endeavour which is to explore the dynamic journey from being to becoming, a process which cannot be accomplished without the necessary awareness.

If the spectator sports—cricket, football and boxing matches—represent challenges both to the individual characters and the entire community, Cozier’s works are much more far-reaching, extending well beyond sports to a more complex psychological approach of character development which in turn hinges on social, moral, political and spiritual development.

If the po-me-one voice is an all too familiar one in much ex-colonial literature—you fail as a writer if your writing is not “black” or self-pitying enough—Cozier, by a mere sleight of hand in his novel PR, turns the tables, flips the coin to reveal another Trinidad—a Trinidad and Tobago of winners who journey, laughing all the way, from being to becoming.